Freitag, 18. März 2011

Yi Women in Liangshan

youjia, 07:38h

Photo by Olivia Kraef.

Talk by Olivia Kraef

Images (Re-) Imbedded:

Yi women and socio-cultural change in Liangshan

Tuesday 22 March, 2011, 8pm at Café Zarah (Gulou Dong Dajie #42)

"How do geographically and culturally peripheral peoples in China deal with the impact of state-defined notions of modernity (economic, cultural) on their own social and cultural environment? This talk introduces the Liangshan Yi (Nuosu), their culture, and issues of contemporary social and cultural change from the vantage point of Yi (Nuosu) women and music."

The talk will be held in English, view here.

Tags für diesen Beitrag 这本文章的标记: Ankündigung 通知, Musik 音乐

... link (0 Kommentare) ... comment

Sonntag, 13. März 2011

Logo Design Competition

youjia, 13:30h

The Himalaya Art Museum launches a global call for their new logo:

"Theme: Himalayas for the Future

Keywords: Continuity, Innovation, Diversity (Multicultural), Nature, Environmentally Conscious

Himalayas art Museum is launching a call for submissions for it’s new logo design. However, the museum is not simply searching for a logo design, but for your vision for the future of the institution. What are your hopes and desires? What challenges do you think we will face? These are the questions we must ask as we move forward in new directions. Thus, we hope to have a logo that will adequately transmit this vision of a new institutional format in a global context.

Designers, artists, critics, curators, and cultural practitioners of all kinds are welcome to submit proposals.

(…)

Submission Deadline: March 10 to April 30, 2011 (Please note that no proposal would be accepted after April 30, 2011)"

More at Himalayas Art Museum.

Tags für diesen Beitrag 这本文章的标记: Ankündigung 通知, Design 设计

"Theme: Himalayas for the Future

Keywords: Continuity, Innovation, Diversity (Multicultural), Nature, Environmentally Conscious

Himalayas art Museum is launching a call for submissions for it’s new logo design. However, the museum is not simply searching for a logo design, but for your vision for the future of the institution. What are your hopes and desires? What challenges do you think we will face? These are the questions we must ask as we move forward in new directions. Thus, we hope to have a logo that will adequately transmit this vision of a new institutional format in a global context.

Designers, artists, critics, curators, and cultural practitioners of all kinds are welcome to submit proposals.

(…)

Submission Deadline: March 10 to April 30, 2011 (Please note that no proposal would be accepted after April 30, 2011)"

More at Himalayas Art Museum.

Tags für diesen Beitrag 这本文章的标记: Ankündigung 通知, Design 设计

... link (0 Kommentare) ... comment

Freitag, 4. März 2011

JUE | Music + Art Festival 2011

youjia, 03:03h

The "independent urban arts and music festival in Shanghai and Beijing. Now in its third year, JUE is a collection of alternative, creative and progressive arts and music events over a three-week period every March, presented by Split Works".

Watch the introduction clip.

March 12 – April 3, 2011 – check it out here.

Tags für diesen Beitrag 这本文章的标记: Ankündigung 通知, Ausstellung 展览, Musik 音乐, Design 设计

... link (0 Kommentare) ... comment

Freitag, 18. Februar 2011

Für euch in Hamburg

youjia, 08:55h

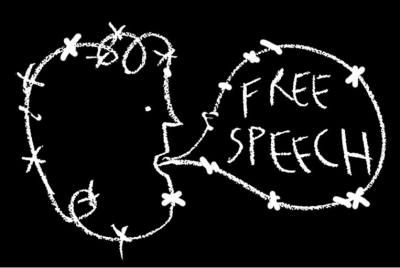

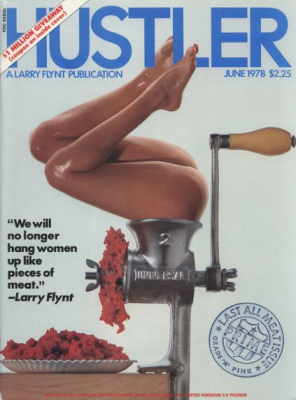

Wobei ihr, die ihr in HH wohnt, vermutlich schon längst davon wisst bzw. dagewesen seid – ich wurde über eine FAZ-Empfehlung darauf aufmerksam. Die aktuelle Ausstellung "Freedom of Speech" im Kunstverein scheint sehr gut zu eurer Rage gegenüber der HH-Kulturpolitik zu passen – vielleicht bewirkt sie etwas …

Hier zwei Screenshots aus der Ankündigungsseite des Kunstvereins:

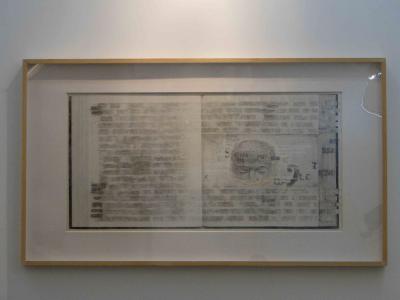

Dan Perjovschi "Free Speech" (2004/2010)

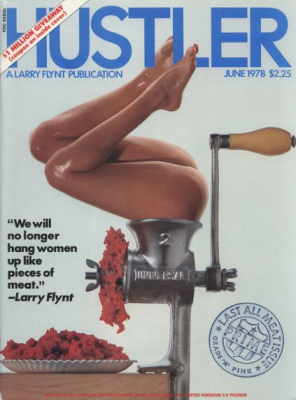

Hustler Magazin, Juni 1978

"Freedom of Speech" läuft im Hamburger Kunstverein bis zum 31. März 2011.

Tags für diesen Beitrag 这本文章的标记: Ankündigung 通知, Ausstellung 展览

Hier zwei Screenshots aus der Ankündigungsseite des Kunstvereins:

Dan Perjovschi "Free Speech" (2004/2010)

Hustler Magazin, Juni 1978

"Freedom of Speech" läuft im Hamburger Kunstverein bis zum 31. März 2011.

Tags für diesen Beitrag 这本文章的标记: Ankündigung 通知, Ausstellung 展览

... link (0 Kommentare) ... comment

Montag, 14. Februar 2011

Future of UCCA

youjia, 13:55h

We knew that the huge UCCA collection has been for sale for a while, now Ullens wants to get ride of the whole space in 798 as well by "looking for long-term partners" – find out more at The Art Newspaper, posted Saturday, 12th of Feb. (linked by Clemens Treter via Facebook). Let us see what will happen – good luck to the employees for now …

Tags für diesen Beitrag 这本文章的标记: Gegenwart 当代, Beijing 北京

Tags für diesen Beitrag 这本文章的标记: Gegenwart 当代, Beijing 北京

... link (0 Kommentare) ... comment

Dienstag, 30. November 2010

"Kultur HEUTE" im Dt.-Cn. Kulturnetz

youjia, 07:38h

Und hier mein Artikel im Deutsch-Chinesischen Kulturnetz als Resümee, das ich aus dem Buch gezogen habe (Überschrift und viele Informationen sind angelehnt an den Artikel "Von der Subkultur zur Kulturindustrie: Die unabhängige Kunstszene" von Sabine Wang in unserem Buch S. 18-28) – 中文在这里:

2000-2010: Von der Subkultur zur Kulturindustrie

Im Mai 2010 fanden erstmals und dann gleich zwei bedeutende Retrospektiven der chinesischen Gegenwartskunst statt. Unter dem Motto Reshaping History präsentierten das Today Art Museum und die Arario Gallery in Peking chinesische Kunst von 2000 bis 2009, im neuen Mingsheng Art Museum in Shanghai ging es sogar um den Zeitraum von 1979 bis 2009 – dem Alter der zeitgenössischen Kunst in China.

Rückblick

Von 1950 bis zum Ende der Kulturrevolution 1976 gab es keine Verbindung zur Außenwelt in China. Die späten 1970er Jahre nach der Öffnung Chinas durch Deng Xiaopings Reformpolitik waren geprägt von künstlerischer Basisarbeit, woraufhin in den 1980ern eine Zeit großer gesellschaftlicher Offenheit folgte. Ausgehend von den Universitäten und mit der Forderung nach Veränderung verknüpft, wurde alles absorbiert, was nach der langen Isolation Chinas endlich wieder zur Verfügung stand, ein Kulturfieber brach aus – die New Wave. Mit dem Schock von 1989, dem harschen Zurechtweisen von offizieller Seite, kam es zu einem Rückfall in den Untergrund, es folgten sowohl eine äußere als auch eine innere Emigration in den 1990er Jahren. Doch auch hier ließ man sich nicht vollständig den Mund verbieten: Die ersten Künstlerkommunen, Beijing East Village und Yuanmingyuan, sowie Ausstellungen in Wohnungen von Freunden und Bekannten als sogenannte Appartement-Art waren damals interessante und experimentelle Orte für Malerei, Performancekunst, Lyrik, Musik und Theater in China. In den ersten Jahren des neuen Jahrtausends befreiten sich dann die Künstler aus der Isolation und begannen, Teil des Establishments zu werden. Die Bildende Kunst kann als das Paradebeispiel für den Wandel der zeitgenössischen Kunstszene von einer Subkultur der 1990er Jahre zur Kulturindustrie in den 2000ern bezeichnet werden – mit dem Künstlerviertel 798 als Inbegriff.

Markpunkt für die kreative Industrialisierung

Heute, im Jahre 2010, sind in den offiziellen Kanon chinesischer Kunst diejenigen Künstler aufgenommen, deren Ausstellungen Ende der 1990er noch durch die Zensurbehörde verboten oder geschlossen wurden. Die damaligen Outcasts wurden zu Pionieren, so manch ein Museumsleiter entstammt der früheren Untergrundszene, zeitgenössische Kunst – zunächst verboten, dann ignoriert – wird nun von der chinesischen Regierung als symbolisches Kapital erkannt. Insbesondere seit Aufstellung des aktuellen Fünf-Jahres-Plans (2006-2010) gilt Soft Power, die sanfte Macht, als neues Schlagwort der Kulturdiplomatie. Die chinesische Regierung hat erkannt, dass sie die Welt nicht ausschließlich mit ökonomischen Leistungen von sich einnehmen kann, was dem kulturellen Sektor einen enormen Aufschwung bescherte. Als ein Markstein für die Kommerzialisierung der Kunst gilt die offizielle Hervorhebung der Kreativindustrie als neuer Wirtschaftszweig im Jahre 2006. Im selben Jahr fand die chinesische Kunst international wirtschaftliche Anerkennung und ihr gelang der kommerzielle Durchbruch: Im Auktionshaus Sotheby’s in New York wurde die erste Auktion chinesischer Gegenwartskunst abgehalten und ein Werk aus der Reihe Bloodlines von Zhang Xiaogang (张晓刚) erzielte dabei die Rekordsumme von knapp einer Million US-Dollar. Euphorie breitete sich aus, der Hype zeitgenössischer chinesischer Kunst brach aus.

Kommerzialisierung und Institutionalisierung

Die Grenzen zwischen unabhängiger und offizieller Kunst begannen zu verschwimmen, seit Ende der 1990er Jahre ist es zu einer langsamen Annährung zwischen den Künstlern und den Vertretern des offiziellen China gekommen – was schließlich zur Kommerzialisierung, aber auch zur Institutionalisierung führte. Mittlerweile ist es nicht mehr unabdingbar, in einen Verband aufgenommen und damit Parteimitglied zu sein, um das Einkommen zu sichern. Die Gunst der Verbände ist nicht mehr die einzige Möglichkeit für Künstler, denn viele Unabhängige haben sich inzwischen mit den Begebenheiten des Marktes arrangiert – nun buhlen die Verbände bereits um Mitglieder und sind angewiesen auf gute Künstler, was Chancen auf eine relative Ausgeglichenheit versprechen lässt. Teilweise kommt es zu Lockerungen der Zensurbestimmungen – wobei die Willkür einzelner Entscheidungsträger weiterhin undurchsichtig bleibt – und unabhängige Produktionsfirmen unter anderem im Film- und Theaterbereich, im Verlagswesen und in der Architektur sind inzwischen erlaubt.

Kulturschaffende müssen sich neben künstlerischen und moralischen Fragen seit diesem Jahrtausend auch mit kommerziellen auseinandersetzen. Die Finanzierung von Kunst und Kultur, die sich nicht selbst trägt, ist zu einem brennenden Thema geworden, es werden dringend weitere Institutionen sowie Stiftungen und ein umfangreiches Kultursponsoring benötigt. Öffentliche Gelder sind knapp bemessen, hinzu kommt die Privatisierung zuvor staatlich subventionierter Einrichtungen, die nun ebenfalls als Konkurrenten auf den Markt treten. So ist es etwa für Theater- und Verlagshäuser wesentlich leichter, den Mainstream zu bedienen, was unabhängige Kunst häufig auf ein Nischendasein beschränkt. Ein Phänomen, das im Westen weidlich bekannt ist und durch Chinas Eintritt in die Marktwirtschaft besonders deutlich zum Vorschein kommt.

Der Weg ins neue Jahrzehnt

Die Nuller-Jahre waren eine rasante Zeit, geprägt von Kommerzialisierung und Globalisierung, von scheinbar uneingeschränkten Möglichkeiten. Die Zeit des kollektiven Gedankenaustausches und Arbeitens innerhalb von Gruppen war vorbei, die Wahrnehmung der chinesischen Künstler als Individuen in der internationalen Szene hatte begonnen – weg von der Verklärung exotischer Romantizismen. „In dem Bedürfnis, ihre Werke einem Publikum zu präsentieren, sind nun die Künstler dabei zu lernen, eine Balance zu schaffen, die ihrer Instrumentalisierung durch die chinesische Regierung standhält“, so Li Zhenhua (李振华), unabhängiger Kurator und Künstler.

Diskussionen der Art, ob der Beginn der Kommerzialisierung der Tod der Avantgarde war und wie Preisanstieg und Quantitätssprung das Schaffen der Künstler beeinflussen, werden nun abgelöst durch Fragen nach der Funktion von Kunst in China, nach dem chinesischen Selbstbewusstsein, den zu vermittelnden Werten und nicht zuletzt nach der Bildung des Publikums. Gefragt sind neben den Künstlern immer dringender auch die Intellektuellen des Landes, von denen allerdings erst verhalten etwas zu hören ist. Nun, zu Beginn der 2010er Jahre, scheint nach dem großen Hype der Vorreiter in der Bildenden Kunst mit internationaler künstlerischer und finanzieller Anerkennung, nach der Wirtschaftskrise, den Olympischen Spielen und auch einhergehend mit dem Jahr des Gedenkens 2009 eine Zeit des Reflektierens und der Selbstbesinnung angebrochen. Die Umsetzung bleibt mit Spannung zu erwarten.

Tags für diesen Beitrag 这本文章的标记: Text 文字, Gegenwart 当代, Häufig gelesen 频看

2000-2010: Von der Subkultur zur Kulturindustrie

Im Mai 2010 fanden erstmals und dann gleich zwei bedeutende Retrospektiven der chinesischen Gegenwartskunst statt. Unter dem Motto Reshaping History präsentierten das Today Art Museum und die Arario Gallery in Peking chinesische Kunst von 2000 bis 2009, im neuen Mingsheng Art Museum in Shanghai ging es sogar um den Zeitraum von 1979 bis 2009 – dem Alter der zeitgenössischen Kunst in China.

Rückblick

Von 1950 bis zum Ende der Kulturrevolution 1976 gab es keine Verbindung zur Außenwelt in China. Die späten 1970er Jahre nach der Öffnung Chinas durch Deng Xiaopings Reformpolitik waren geprägt von künstlerischer Basisarbeit, woraufhin in den 1980ern eine Zeit großer gesellschaftlicher Offenheit folgte. Ausgehend von den Universitäten und mit der Forderung nach Veränderung verknüpft, wurde alles absorbiert, was nach der langen Isolation Chinas endlich wieder zur Verfügung stand, ein Kulturfieber brach aus – die New Wave. Mit dem Schock von 1989, dem harschen Zurechtweisen von offizieller Seite, kam es zu einem Rückfall in den Untergrund, es folgten sowohl eine äußere als auch eine innere Emigration in den 1990er Jahren. Doch auch hier ließ man sich nicht vollständig den Mund verbieten: Die ersten Künstlerkommunen, Beijing East Village und Yuanmingyuan, sowie Ausstellungen in Wohnungen von Freunden und Bekannten als sogenannte Appartement-Art waren damals interessante und experimentelle Orte für Malerei, Performancekunst, Lyrik, Musik und Theater in China. In den ersten Jahren des neuen Jahrtausends befreiten sich dann die Künstler aus der Isolation und begannen, Teil des Establishments zu werden. Die Bildende Kunst kann als das Paradebeispiel für den Wandel der zeitgenössischen Kunstszene von einer Subkultur der 1990er Jahre zur Kulturindustrie in den 2000ern bezeichnet werden – mit dem Künstlerviertel 798 als Inbegriff.

Markpunkt für die kreative Industrialisierung

Heute, im Jahre 2010, sind in den offiziellen Kanon chinesischer Kunst diejenigen Künstler aufgenommen, deren Ausstellungen Ende der 1990er noch durch die Zensurbehörde verboten oder geschlossen wurden. Die damaligen Outcasts wurden zu Pionieren, so manch ein Museumsleiter entstammt der früheren Untergrundszene, zeitgenössische Kunst – zunächst verboten, dann ignoriert – wird nun von der chinesischen Regierung als symbolisches Kapital erkannt. Insbesondere seit Aufstellung des aktuellen Fünf-Jahres-Plans (2006-2010) gilt Soft Power, die sanfte Macht, als neues Schlagwort der Kulturdiplomatie. Die chinesische Regierung hat erkannt, dass sie die Welt nicht ausschließlich mit ökonomischen Leistungen von sich einnehmen kann, was dem kulturellen Sektor einen enormen Aufschwung bescherte. Als ein Markstein für die Kommerzialisierung der Kunst gilt die offizielle Hervorhebung der Kreativindustrie als neuer Wirtschaftszweig im Jahre 2006. Im selben Jahr fand die chinesische Kunst international wirtschaftliche Anerkennung und ihr gelang der kommerzielle Durchbruch: Im Auktionshaus Sotheby’s in New York wurde die erste Auktion chinesischer Gegenwartskunst abgehalten und ein Werk aus der Reihe Bloodlines von Zhang Xiaogang (张晓刚) erzielte dabei die Rekordsumme von knapp einer Million US-Dollar. Euphorie breitete sich aus, der Hype zeitgenössischer chinesischer Kunst brach aus.

Kommerzialisierung und Institutionalisierung

Die Grenzen zwischen unabhängiger und offizieller Kunst begannen zu verschwimmen, seit Ende der 1990er Jahre ist es zu einer langsamen Annährung zwischen den Künstlern und den Vertretern des offiziellen China gekommen – was schließlich zur Kommerzialisierung, aber auch zur Institutionalisierung führte. Mittlerweile ist es nicht mehr unabdingbar, in einen Verband aufgenommen und damit Parteimitglied zu sein, um das Einkommen zu sichern. Die Gunst der Verbände ist nicht mehr die einzige Möglichkeit für Künstler, denn viele Unabhängige haben sich inzwischen mit den Begebenheiten des Marktes arrangiert – nun buhlen die Verbände bereits um Mitglieder und sind angewiesen auf gute Künstler, was Chancen auf eine relative Ausgeglichenheit versprechen lässt. Teilweise kommt es zu Lockerungen der Zensurbestimmungen – wobei die Willkür einzelner Entscheidungsträger weiterhin undurchsichtig bleibt – und unabhängige Produktionsfirmen unter anderem im Film- und Theaterbereich, im Verlagswesen und in der Architektur sind inzwischen erlaubt.

Kulturschaffende müssen sich neben künstlerischen und moralischen Fragen seit diesem Jahrtausend auch mit kommerziellen auseinandersetzen. Die Finanzierung von Kunst und Kultur, die sich nicht selbst trägt, ist zu einem brennenden Thema geworden, es werden dringend weitere Institutionen sowie Stiftungen und ein umfangreiches Kultursponsoring benötigt. Öffentliche Gelder sind knapp bemessen, hinzu kommt die Privatisierung zuvor staatlich subventionierter Einrichtungen, die nun ebenfalls als Konkurrenten auf den Markt treten. So ist es etwa für Theater- und Verlagshäuser wesentlich leichter, den Mainstream zu bedienen, was unabhängige Kunst häufig auf ein Nischendasein beschränkt. Ein Phänomen, das im Westen weidlich bekannt ist und durch Chinas Eintritt in die Marktwirtschaft besonders deutlich zum Vorschein kommt.

Der Weg ins neue Jahrzehnt

Die Nuller-Jahre waren eine rasante Zeit, geprägt von Kommerzialisierung und Globalisierung, von scheinbar uneingeschränkten Möglichkeiten. Die Zeit des kollektiven Gedankenaustausches und Arbeitens innerhalb von Gruppen war vorbei, die Wahrnehmung der chinesischen Künstler als Individuen in der internationalen Szene hatte begonnen – weg von der Verklärung exotischer Romantizismen. „In dem Bedürfnis, ihre Werke einem Publikum zu präsentieren, sind nun die Künstler dabei zu lernen, eine Balance zu schaffen, die ihrer Instrumentalisierung durch die chinesische Regierung standhält“, so Li Zhenhua (李振华), unabhängiger Kurator und Künstler.

Diskussionen der Art, ob der Beginn der Kommerzialisierung der Tod der Avantgarde war und wie Preisanstieg und Quantitätssprung das Schaffen der Künstler beeinflussen, werden nun abgelöst durch Fragen nach der Funktion von Kunst in China, nach dem chinesischen Selbstbewusstsein, den zu vermittelnden Werten und nicht zuletzt nach der Bildung des Publikums. Gefragt sind neben den Künstlern immer dringender auch die Intellektuellen des Landes, von denen allerdings erst verhalten etwas zu hören ist. Nun, zu Beginn der 2010er Jahre, scheint nach dem großen Hype der Vorreiter in der Bildenden Kunst mit internationaler künstlerischer und finanzieller Anerkennung, nach der Wirtschaftskrise, den Olympischen Spielen und auch einhergehend mit dem Jahr des Gedenkens 2009 eine Zeit des Reflektierens und der Selbstbesinnung angebrochen. Die Umsetzung bleibt mit Spannung zu erwarten.

Tags für diesen Beitrag 这本文章的标记: Text 文字, Gegenwart 当代, Häufig gelesen 频看

... link (0 Kommentare) ... comment

Mittwoch, 17. November 2010

Auf Kunstreise in Shanghai

youjia, 18:54h

Hier ein paar Eindrücke einer Kunstreise durch Shanghai und Beijing vom 8.-14. September 2010 – etwas länger, da dieser Blog eine Weile still stand, hier zunächst die Tour durch Shanghai:

Mittwoch, 8. September 2010

SHCONTEMPORARY

- Shanghai Exhibition Center 上海展览中心

- Adresse: 1000 Yan’an Zhong Lu 延安中路1000号

- www.shcontemporary.info/English/event/welcome

- Direktor: Colin Chinnery

Themen

- Re-Value: „artistic evolution from traditional to modern to contemporary“

- Asiatische Gegenwartskunst sammeln

o China ist mittlerweile der 3. größte Kunstmarkt nach den USA und England

- Giorgio Morandi (Einfluss auf moderne und ggw. cn. Kunst)

o 1890-1964, ital. Maler und Grafiker, bekannt für seine Stillleben

o kontemplative und introspektive Stillleben, Landschaftsmalerei, Stiche, Radierungen

Exponate (Auswahl)

„Hype-Art“ (Pop-Art etc.) der Nuller-Jahre

usw.

usw.

PA TA Gallery Beijing, Taipei

Neues entsteht – „The show must go on“

Art Statements

Art Labor Gallery Shanghai

55 Shanghai

Zang Kunkun: Ohne Titel

Grafik

Kalfayan Galleries: Antonis Donef

Hangzhou Renke Arts

Hanmo Art Gallery

White Space Beijing: Miao Xiaochuns „Transport“ und „Greed

Anima

Taikang Space: Yang Mao-Lin

Art Seasons

Art Statements: Yoshitaka Amanos „Deva Loka

Nightmare“

Traditionelle Malerei im neuen Gewand

Art for All Society Macau, Beijing

Gallery Maek-Hyang: Li Dingxiong

Gallery Artside: Oh Yeun Seoks „The Song of Lady“

Christine Park Paris

Cai Xiaosong

Fotografie (in Anlehnung an traditionelle Malerei)

55 Shanghai

Paris-Beijing Galerie: Yang Yongliangs „Artificial Wonderland“

Dimensional Art

Arario Gallery Beijing

Pékin Fine Arts: Jin Shan

Art Issue Projects

Art Issue Projects

Arario Gallery Beijing

White Space Beijing

Skulpturesk

Gallery Hyundai

DNA Berlin

Hanmo Art Gallery

Art Issue Projects

55 Shanghai

DNA Berlin

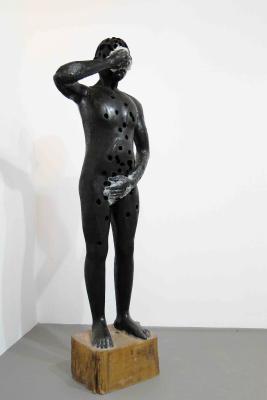

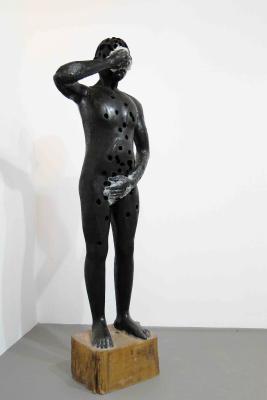

Arario Gallery Beijing: Tallur L. N.s „Man with Holes“

White Space Beijing: Wang Shugang

Liu Jiawei

Galerien (weitere Auswahl)

- Art Issue Projects, Beijing

o vorher Han Ji Yun Contemporary Space, jetzt Zus.schluss mit Art Issue Magazine

o neue engl.-cn. Kunstzeitschrift aus Beijing

o Fokus: Ggw.skunst China

- Boers-Li, Beijing

o Lin Chuang (Jingshan, 1978)

o gegründet 2005, Fokus: Installationen, Skulpturen, Malerei, Arbeiten auf Papier, Audioarbeiten, Fotografie, Video, Film, Performance, Digitalkunst

- Galleria Continua, Beijing

o Italien, gegründet 2004 im 798

- Long March Space, Beijing

o Zhu Yu (Chengdu, 1970): „controversial; focusing on moral and religious issues between humanity and divinity“

o gegründet 2002, Fokus: „dedicated to the fundamental questions of the relationship between curating, display and artistic creation, between practice and discourse, between objects and text, and between audience and artists“

- Alexander Ochs Galleries, Beijing, Berlin

o gegründet 1997 mit Asienbezug in Berlin, 2008 in Beijing

- White Space, Beijing

o gegründet 2004, Fokus: „emerging Chinese contemporary arts“

- PLATFORM China, Beijing

o gegründet 2005, Fokus: „develop and promote contemporary art in China and to build up a platform of cultural exchange and dialogue between Chinese and international artists“

- ShanghART, Shanghai, Beijing

o Sun Xun (Fuxin, 1980): produces a multitude of drawings that incorporate text within the image for his animation

o Zhao Bandi (BJ, 1966): Panda-Serien

o Initiiert 1996, Fokus: „one of China’s most influential contemporary art institutions“

- Tang Contemporary Art, Beijing

o Chen Wenbo (Chongqing, 1969): Mitglied der LM100 Creative Community

Freitag, 10. September 2010

ROCKBUND ART MUSEUM

- Adresse: 20 Huqiu Road, Huangpu District, Shanghai 200002, 黄浦区虎丘路20号 Tel: 021-3310 9985

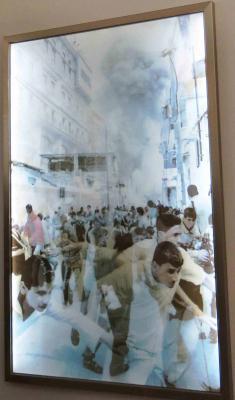

- dies ist die zweite Ausstellung des gerade neu eröffneten Museums (inszwischen läuft die dritte Ausstellung: By Day, By Night, or Some (Special) Things a Museum Can Do). Zuvor gab es eine Ausstellung von Cai Guoqiang, einem sozialkritischen, sehr wichtigen und interessanten cn. Künstler. Beim letzten Mal wurde ein Teil der alten Bank mit als Ausstellungsfläche inkl. der alten Räumlichkeiten der Schließfächer verwendet, diese ist eine Kirche in der Nähe integriert

- ein wirklich spannendes neues Museum für Shanghai

- Ausstellung: Zeng Fanzhi „Unexpected Acts of Uncertain Consequence“ (Wuhan, 1964, lebt in BJ); einige Hintergrundinformationen zum Künstler:

o bekannt wurde Zeng mit der Porträtserie „Masks“, Landsleute Mitte der 1990er (Veränderung an der Oberfläche)

o Überpräsenz Mao Zedongs (Werk: „Tian’anmen“), weitere Werke von Marx, Engels, Stalin, Lenin

o Porträts, bäuerliche Landschaftsmalerei, politisch aufgeladene Motive, Alltag, überdimensionale Hände und stereotype Gesichter

o weitere Themen: Banalität und Trauma; Schalheit öffentlichen Raumes, die sich zermahlenden Massen; Seelenqual; Parodien zwischen Gedanken und Handeln; geisterhafte Abbilder als Echo von Mehrdeutigkeit und technischer Transformation

o Einfluss: dt. Expressionismus, später Song-Dynastie (kalligraphisch-romantisch); Studentenzeit in Wuhan mit Toilettenbenutzung des nahen Krankenhauses, Anblicke der Schlachter in seiner Straße

o viele cn. Künstle haben amerik. Popkunst aufgegriffen und sie in sozialen Realismus eingebunden als Kommentar der sich schnell verändernden cn. Gesellschaft – Zeng Fanzhi sticht hervor durch die introspektive Art seiner Arbeiten, mit der er häufig das persönliche Leben und seine Emotionen reflektiert, immer seine eigenen Gefühle porträtierend; ideologische Veränderungen haben ihn nichtsdestoweniger geprägt; er erfindet sich ständig neu; Idealismus und eine gewisse Traurigkeit, dass dieser nicht erfüllt werden kann

o Kompositionen zwischen Ironie und Optimismus, Fusion der Verehrung revolutionären Heroismus und ungewissen, sich rapide entwickelnden Zukunft; provokative Sensationslust, unterschwellige Gewalt, psychologische Spannung, übernatürliche Aura

o arbeitet gelegentlich simultan mit 2 Pinsel (gleichzeitiges Kreieren und Zerstören), mit einem, um das Subjekt zu beschreiben, während der andere Spuren auf der Leinwand des unterbewussten Malprozesses hinterlässt; Landschaftsmalerei so etwa Transformation in Abstraktion, die abgebildeten Personen fließen zus. in Erinnerung und Imagination

o eine Frage zur Sponsorenschaft Zengs kam auf: er stiftet jährlich 120 tsd. RMB an seine ehem. Kunstschule in Wuhan, 100 tsd. RMB an die Beida; nach dem Erdbeben im Mai 2008 in Sichuan hat er 370 tsd. RMB für ein Projekt zur Förderung behinderter Kinder zum Eintritt in Kunstschulen bereitgestellt

--> diese Art der Ausbildungsförderung ist nichts außergewöhnliches, besonders nicht für einen Künstler, der es v. a. auch im materiellen Sinne „geschafft“ hat

PEARL LAM CONTRASTS GALLERY

- Adresse: 黄浦区江西中路181号, 021-6323 1988

- gegründet 1996, vertreten in London, Paris, New York, Tokyo, Los Angeles und Shanghai, um bld. Kunst, Architektur und Design in Beziehung zu setzen

- Ausstellung: Li Tianbing „Childhood Fantasy“ (Guilin, 1974, lebt in Paris); einige Hintergrundinformationen zum Künstler:

o traditionelle cn. Malerei mit Elementen westlicher Ikonografie

o gesellschaftskritische Aspekte der Konsumgesellschaft, Veränderung kultureller Werte

o wichtige Serien: „LC Body“ und „Me and My Brother“; elegante und subtile Verbindung kultureller Einflüsse (Ost-West) mit dekonstruktiven Elementen unterschwelliger Gewalt

o „Childhood Fantasy“: Kindergesichter mit Symbolen bekannter Industriekonzerne oder bekannten Textzeilen (Internet, Zeitung); verwitterte, rissige Bildoberflächen; Absage an den Gebrauch von Farbe; Kommentar an ggw. Familienpolitik in China; atmosphärische Werke stilistischer Variationen; fernöstliche Philosophie der Grundidee stetiger Weiterentwicklung des Selbst

o Unvollkommenheit der Konservierung der Vergangenheit; Spannung zwischen fotografischer und dokumentarischer Belege, Erfassung von Erinnerung konstruierter (auch fiktiver), physikalischer Objekte

o zwei Herangehensweisen an die menschliche Existenz, deren Weg nicht kontrolliert werden kann, aber deren Verständnis ständig erweitert werden kann, mit dem Leben, das aus unterschiedlichen Facetten zusammengefügt ist, äußeren Einflüssen unterliegt und sich in Bewegung befindet; Teil dessen seiend kann akzeptiert werden oder wir können und mit der Anpassung abmühen – die vergänglich und illusorisch ist

SHANGHAI GALLERY OF ART, THREE ON THE BUND

- Adresse: 3rd Floor, No.3, the Bund 中山东一路三号三楼, 021-6321 5757, 6323 3355

- gegründet 2004 mit dem Anspruch, wichtige cn. Ggwts.künstler zurück nach China zu holen, um die Geschichte Chinas zu bewahren

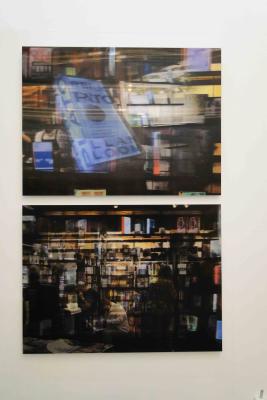

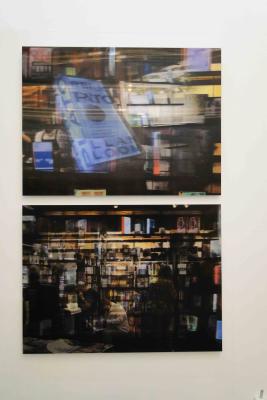

- aktuelle Ausstellung: Feng Mengbo „Journey to the West“ (Beijing, 1966); einige Hintergrundinformationen zum Künstler:

o Feng Mengbo ist ein Video- und Installationskünstler

o seine Arbeit „Q4U“, eine künstlerisch bearbeitete Version des Egoshooters Quake III, war 2002 auf der Documenta zu sehen

o 2004 wurde ihm der Kulturpreis Prix Ars Electronica für „Ah_Q – A Mirror of Death“ überreicht

o „Die Reise in den Westen“ ist einer der chin. literarischen Klassiker (insg. 4, dieser aus der Ming-Dynastie im 16. Jhd. von Wu Cheng’en)

--> Geschichte der Reise des Mönches Xuanzang zum westlichen Himmel, im heutigen Indien, von wo er Buddhas heilige Schriften nach China bringen soll – reale Begebenheit aus dem 7. Jhd.; begleitet wird er von Gefährten, von einem Wasserdämon, einem Menschen, der in ein Schwein verwandelt wurde und vom König der Affen Sun Wukong – dem eigentlichen Hauptcharakter der Geschichte

o Zus.fügung aus seinem Interesse an digitaler Kunst und Tradition, klassische spirituelle Werte sind überführt in die Cyberrealität Fengs

o idyllische Landschaften sind mit 3D-Programmen bearbeitet, dazu kommt ein interaktives Videospiel mit Gaming Hard- und Software

o Themen: Kommerz, Tradition

Three on the Bund mit Blick über den Bund

STUDIOBESUCH VON WU SHANZHUAN UND INGA SVALA THORSDOTTIR, PUDONG

- Wu Shanzhuan (Zhoushan, 1960, lebt in Hamburg und Shanghai), spricht Dt. und Engl.

- international anerkannter Konzeptkünstler, ein Freund von Bruno Bischofberger

- bekannt als einer der Vorreiter der cn. Konzeptbewegung in den 1980ern, war Wu der erste Künstler in China, der Textteile von Popanspielungen in seine Werke aufgenommen hat. Damals kristallisierte sich auch sein äußerst idiosynkratischer Ansatz der Malerei heraus, den er mit politischen Aussagen, religiösen Schriften und Werbeslogans kombiniert

- Wus Leinwände erscheinen als eine Kombination aus Graffiti und Expressionismus; zus.gefügt aus Wörtern, Symbolen, Diagrammen, die um den Platz auf seinen Werken zu wetteifern scheinen – virtuell auf der Wand und in piktografischer Abstraktion

- durch die Verwendung der Symbole entzieht er ihnen ihren urspr. Kontext und ihre kulturelle Bedeutung – wobei diese natürlich immer oberflächlich mitspielen –, er entleert sie durch den Massengebrauch an Farbe und Schrift, reinigt sie für den Neugebrauch und zur Kontemplation

- Wu geht den Prozess des Malens als Schreiben, exemplarisch etwa in seiner Serie „Today No Water“ von 2007. Als grafischer Roman angelegt, bildet jede Leinwand ein Kapitel einer sich aufbauenden Erzählung. Zugrunde liegt dem keine Storyline, sondern vielmehr eine visuelle Spannkraft zwischen fragmentarischen Phrasen und Bildern, die in einer Gesamtkomposition von Freestyle Assoziationen und Ideen, Referenzen und Symbolen zus.kommen

MOGANSHAN ART DISTRICT

- Adresse: 普陀区莫干山路50号

- das Moganshan, genannt M50 nach seiner Lage auf der Moganshan Road Nr. 50, ist das Künstlerviertel von Shanghai – ähnlich dem 798 in Beijing

- vor 10 Jahren zogen die ersten Künstler und Galerien in eine alte Textilfabrik in das Moganshan 50. Der Komplex war jahrelang vom Abriss bedroht, während sich in nächster Nachbarschaft Hochhäuser in die Höhe schraubten. In den letzten Jahren entwickelte sich dann in der 50 Moganshan Road eine Kunstoase, die schließlich immer kommerzieller wurde und dadurch ihr Bestehen sichern konnte

- das 10. Jubiläum des Viertels beginnt seine Eröffnungsfeier heute und geht bis in den Oktober hinein

- ShanghART, Shanghai, Beijing

o initiiert 1996 von Lorenz Helbling, gilt als eine der einflussreichsten Institutionen der Ggwts.kunst in China

o aktuelle Ausstellungen:

--> Sun Xun (Fuxin, 1980): New Media-Künstler; produziert eine Vielzahl von Werken, die Textpassagen in den Bildern seiner Anima aufnehmen; er beschäftigt sich mit Weltgeschichte und Politik, sowie mit lebenden Organismen

--> Zhao Bandi (BJ, 1966): bekannt für seine Panda-Serien als Parodie auf die offizielle cn. Propaganda, durch das Nationaltier spricht Zhao auch auf der ShContemporary unter den „Discoveries“, dort hat er seine Werke von den beiden Kindern vorstellen lassen

o. A.

Madeln „Spread 201009103“ (2010)

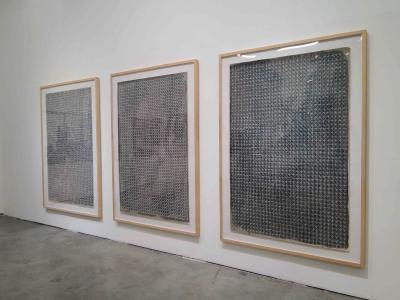

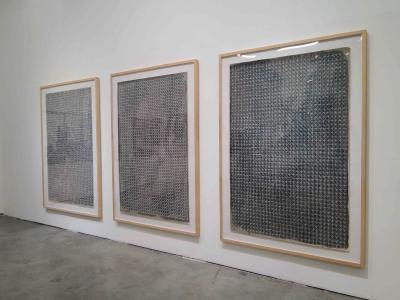

Ding Yi „Appearance of Crosses 2007-8-04/ 01/ 03“ (v.l.n.r., 2007)

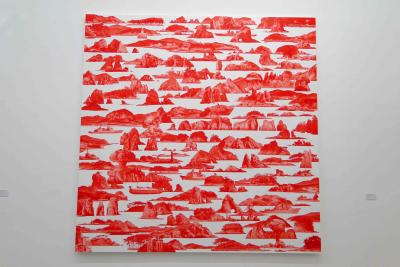

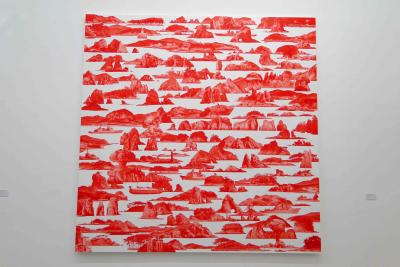

Yang Zhenzhong „No. 01 – No. 25“ (2010)

- Galerieempfehlungen zum 10. Jub. des M50

o Loh Gallery, Moganshan Bldg. 3/ 111: Galerieeröffnung 19 Uhr

o Madeln Space, Moganshan Bldg. 7/ 4. Stk., Eröffnung Li Ming, Lin Ke, Yang Junling: „Dedicated to Money Makers“, 18 Uhr

o Vanguard Gallery, Moganshan Bldg. 4A/ 204, Ausstellung Xu Di: „Vivid as Fruit“

Samstag, 11. September 2010

PRIVATSAMMLUNG VON QIAO ZHIBIN

- Sammler mit eigenen KTV-Clubs in Beijing und Shanghai

Ding Yi

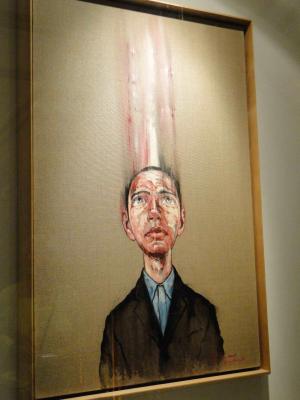

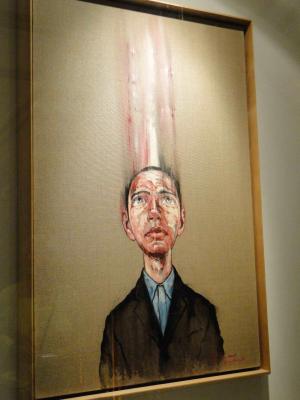

Zeng Fanzhi

Aoyama Satoru

MINSHENG ART MUSEUM/ RED TOWN

- Adresse: Red Town, 570 Huaihai Xi Lu, Xuhui District 淮海西路570号,近凯旋路, Tel: 021-6280-4741, 6280-9231

o wie das Rockbund ist das Minsheng ein neues Museum mit der zweiten Ausstellung.

Es ist benannt nach seinem „Gründer“, der Minsheng Bank – das Museum ist das erste seiner Art in China, das von einer Bank gegründet wurde. Die erste Ausstellung hatte sehr große Ziele verfolgt, es handelte sich um eine Retrospektive der chin. Kunst der letzten 30 Jahre – leider wirkte es etwas willkürlich bzw. schien es, als wären die Werke ausgestellt, die gerade zur Verfügung standen oder von befreundeten Künstlern zur Verfügung gestellt wurden

- aktuelle Ausstellung: Korean Contemporary Art „Plastic Garden“

o „Plastic Garden“ ist eine Ausstellung von 17 koreanischen Künstlern mit 64 Werken

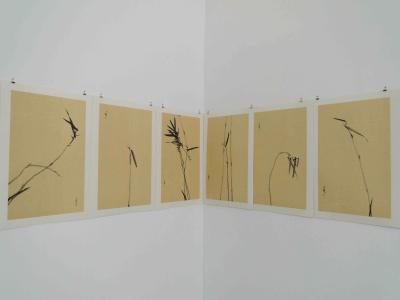

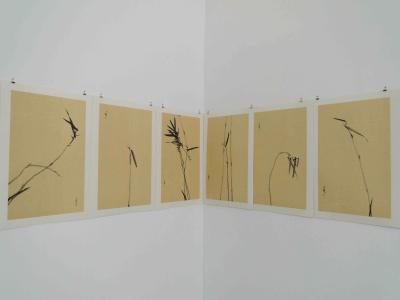

o Gemeinsamkeiten liegen eindeutig in der verbindenden asiatischen Tradition der Kalligraphie und des kontemplativen, buddhistischen Ansatzes; in der Vorstellung der Lehre des Nichts

Noh Sang Kyoon

Yongbaek Lee

Lee Seahyun

Chung Suejin

Jung Yeondoo

Ham Jin

RED TOWN: „SCULPTURE PARK“ UND „SCULPTURE SPACE“

- Regelmäßig wechselnde Skulpturen

- Red Town war urspr. eine Stahlfabrik und ist seit seiner „Neugründung“ 2005 zu einer der Zentren der Kreativindustrie Shanghais geworden (mit allem, was dazugehört, Designfirmen, Cafés, Galerien etc.)

WEITERE GALERIEN

- 140 sqm

o Galerie von Liu Yingmei, aktuell: Ai Weiwei und Zhang Peili

o Adresse: 1331 Fuxing Zhonglu, 26 Room, near Fenyang Lu 复兴中路1331号26室,汾阳路口, 021-6431 6216

- Zendai Himalayan Art Center

o aktuell: „Updating China for a Sustainable Future“ (dt.-cn. EXPO-Show)

o No. 28 Lane 199, Fangdian Lu 芳甸路199弄28号, 021-5033 9801

- MoCA Shanghai

o aktuell: Umbau für Eröffnung „Reflection of Minds“ am 12.9.

o Adresse: People's Park, 231 Nanjing West Road 人民公园南京西路231号,021-6327 9900

- Shanghai Duolun Museum of Modern Art

o aktuell: Saudi Arabien

o Adresse: No. 27 Duolun Road 多伦路27号, 021-6587 2530, 6587 5996

- Zhu Qizhan Art Museum

o aktuell: Poetry of Russian Soul

o Adresse: No. 580 Ouyang Road, 欧阳路580号, 021-5671 0742, 5671 0741

140sqm: Ai Weiweis Skulptur zur „Fuck Off“-Fotografieserie (2006)

Fan Jiupeng (2010)

Art Labor Gallery: Ying Yefus „Sweet and Sour“ (2010)

Tags für diesen Beitrag 这本文章的标记: Reise 专程, Künstler 艺术家, Ausstellung 展览, Gegenwart 当代, Häufig gelesen 频看

Mittwoch, 8. September 2010

SHCONTEMPORARY

- Shanghai Exhibition Center 上海展览中心

- Adresse: 1000 Yan’an Zhong Lu 延安中路1000号

- www.shcontemporary.info/English/event/welcome

- Direktor: Colin Chinnery

Themen

- Re-Value: „artistic evolution from traditional to modern to contemporary“

- Asiatische Gegenwartskunst sammeln

o China ist mittlerweile der 3. größte Kunstmarkt nach den USA und England

- Giorgio Morandi (Einfluss auf moderne und ggw. cn. Kunst)

o 1890-1964, ital. Maler und Grafiker, bekannt für seine Stillleben

o kontemplative und introspektive Stillleben, Landschaftsmalerei, Stiche, Radierungen

Exponate (Auswahl)

„Hype-Art“ (Pop-Art etc.) der Nuller-Jahre

usw.

usw.PA TA Gallery Beijing, Taipei

Neues entsteht – „The show must go on“

Art Statements

Art Labor Gallery Shanghai

55 Shanghai

Zang Kunkun: Ohne Titel

Grafik

Kalfayan Galleries: Antonis Donef

Hangzhou Renke Arts

Hanmo Art Gallery

White Space Beijing: Miao Xiaochuns „Transport“ und „Greed

Anima

Taikang Space: Yang Mao-Lin

Art Seasons

Art Statements: Yoshitaka Amanos „Deva Loka

Nightmare“

Traditionelle Malerei im neuen Gewand

Art for All Society Macau, Beijing

Gallery Maek-Hyang: Li Dingxiong

Gallery Artside: Oh Yeun Seoks „The Song of Lady“

Christine Park Paris

Cai Xiaosong

Fotografie (in Anlehnung an traditionelle Malerei)

55 Shanghai

Paris-Beijing Galerie: Yang Yongliangs „Artificial Wonderland“

Dimensional Art

Arario Gallery Beijing

Pékin Fine Arts: Jin Shan

Art Issue Projects

Art Issue Projects

Arario Gallery Beijing

White Space Beijing

Skulpturesk

Gallery Hyundai

DNA Berlin

Hanmo Art Gallery

Art Issue Projects

55 Shanghai

DNA Berlin

Arario Gallery Beijing: Tallur L. N.s „Man with Holes“

White Space Beijing: Wang Shugang

Liu Jiawei

Galerien (weitere Auswahl)

- Art Issue Projects, Beijing

o vorher Han Ji Yun Contemporary Space, jetzt Zus.schluss mit Art Issue Magazine

o neue engl.-cn. Kunstzeitschrift aus Beijing

o Fokus: Ggw.skunst China

- Boers-Li, Beijing

o Lin Chuang (Jingshan, 1978)

o gegründet 2005, Fokus: Installationen, Skulpturen, Malerei, Arbeiten auf Papier, Audioarbeiten, Fotografie, Video, Film, Performance, Digitalkunst

- Galleria Continua, Beijing

o Italien, gegründet 2004 im 798

- Long March Space, Beijing

o Zhu Yu (Chengdu, 1970): „controversial; focusing on moral and religious issues between humanity and divinity“

o gegründet 2002, Fokus: „dedicated to the fundamental questions of the relationship between curating, display and artistic creation, between practice and discourse, between objects and text, and between audience and artists“

- Alexander Ochs Galleries, Beijing, Berlin

o gegründet 1997 mit Asienbezug in Berlin, 2008 in Beijing

- White Space, Beijing

o gegründet 2004, Fokus: „emerging Chinese contemporary arts“

- PLATFORM China, Beijing

o gegründet 2005, Fokus: „develop and promote contemporary art in China and to build up a platform of cultural exchange and dialogue between Chinese and international artists“

- ShanghART, Shanghai, Beijing

o Sun Xun (Fuxin, 1980): produces a multitude of drawings that incorporate text within the image for his animation

o Zhao Bandi (BJ, 1966): Panda-Serien

o Initiiert 1996, Fokus: „one of China’s most influential contemporary art institutions“

- Tang Contemporary Art, Beijing

o Chen Wenbo (Chongqing, 1969): Mitglied der LM100 Creative Community

Freitag, 10. September 2010

ROCKBUND ART MUSEUM

- Adresse: 20 Huqiu Road, Huangpu District, Shanghai 200002, 黄浦区虎丘路20号 Tel: 021-3310 9985

- dies ist die zweite Ausstellung des gerade neu eröffneten Museums (inszwischen läuft die dritte Ausstellung: By Day, By Night, or Some (Special) Things a Museum Can Do). Zuvor gab es eine Ausstellung von Cai Guoqiang, einem sozialkritischen, sehr wichtigen und interessanten cn. Künstler. Beim letzten Mal wurde ein Teil der alten Bank mit als Ausstellungsfläche inkl. der alten Räumlichkeiten der Schließfächer verwendet, diese ist eine Kirche in der Nähe integriert

- ein wirklich spannendes neues Museum für Shanghai

- Ausstellung: Zeng Fanzhi „Unexpected Acts of Uncertain Consequence“ (Wuhan, 1964, lebt in BJ); einige Hintergrundinformationen zum Künstler:

o bekannt wurde Zeng mit der Porträtserie „Masks“, Landsleute Mitte der 1990er (Veränderung an der Oberfläche)

o Überpräsenz Mao Zedongs (Werk: „Tian’anmen“), weitere Werke von Marx, Engels, Stalin, Lenin

o Porträts, bäuerliche Landschaftsmalerei, politisch aufgeladene Motive, Alltag, überdimensionale Hände und stereotype Gesichter

o weitere Themen: Banalität und Trauma; Schalheit öffentlichen Raumes, die sich zermahlenden Massen; Seelenqual; Parodien zwischen Gedanken und Handeln; geisterhafte Abbilder als Echo von Mehrdeutigkeit und technischer Transformation

o Einfluss: dt. Expressionismus, später Song-Dynastie (kalligraphisch-romantisch); Studentenzeit in Wuhan mit Toilettenbenutzung des nahen Krankenhauses, Anblicke der Schlachter in seiner Straße

o viele cn. Künstle haben amerik. Popkunst aufgegriffen und sie in sozialen Realismus eingebunden als Kommentar der sich schnell verändernden cn. Gesellschaft – Zeng Fanzhi sticht hervor durch die introspektive Art seiner Arbeiten, mit der er häufig das persönliche Leben und seine Emotionen reflektiert, immer seine eigenen Gefühle porträtierend; ideologische Veränderungen haben ihn nichtsdestoweniger geprägt; er erfindet sich ständig neu; Idealismus und eine gewisse Traurigkeit, dass dieser nicht erfüllt werden kann

o Kompositionen zwischen Ironie und Optimismus, Fusion der Verehrung revolutionären Heroismus und ungewissen, sich rapide entwickelnden Zukunft; provokative Sensationslust, unterschwellige Gewalt, psychologische Spannung, übernatürliche Aura

o arbeitet gelegentlich simultan mit 2 Pinsel (gleichzeitiges Kreieren und Zerstören), mit einem, um das Subjekt zu beschreiben, während der andere Spuren auf der Leinwand des unterbewussten Malprozesses hinterlässt; Landschaftsmalerei so etwa Transformation in Abstraktion, die abgebildeten Personen fließen zus. in Erinnerung und Imagination

o eine Frage zur Sponsorenschaft Zengs kam auf: er stiftet jährlich 120 tsd. RMB an seine ehem. Kunstschule in Wuhan, 100 tsd. RMB an die Beida; nach dem Erdbeben im Mai 2008 in Sichuan hat er 370 tsd. RMB für ein Projekt zur Förderung behinderter Kinder zum Eintritt in Kunstschulen bereitgestellt

--> diese Art der Ausbildungsförderung ist nichts außergewöhnliches, besonders nicht für einen Künstler, der es v. a. auch im materiellen Sinne „geschafft“ hat

PEARL LAM CONTRASTS GALLERY

- Adresse: 黄浦区江西中路181号, 021-6323 1988

- gegründet 1996, vertreten in London, Paris, New York, Tokyo, Los Angeles und Shanghai, um bld. Kunst, Architektur und Design in Beziehung zu setzen

- Ausstellung: Li Tianbing „Childhood Fantasy“ (Guilin, 1974, lebt in Paris); einige Hintergrundinformationen zum Künstler:

o traditionelle cn. Malerei mit Elementen westlicher Ikonografie

o gesellschaftskritische Aspekte der Konsumgesellschaft, Veränderung kultureller Werte

o wichtige Serien: „LC Body“ und „Me and My Brother“; elegante und subtile Verbindung kultureller Einflüsse (Ost-West) mit dekonstruktiven Elementen unterschwelliger Gewalt

o „Childhood Fantasy“: Kindergesichter mit Symbolen bekannter Industriekonzerne oder bekannten Textzeilen (Internet, Zeitung); verwitterte, rissige Bildoberflächen; Absage an den Gebrauch von Farbe; Kommentar an ggw. Familienpolitik in China; atmosphärische Werke stilistischer Variationen; fernöstliche Philosophie der Grundidee stetiger Weiterentwicklung des Selbst

o Unvollkommenheit der Konservierung der Vergangenheit; Spannung zwischen fotografischer und dokumentarischer Belege, Erfassung von Erinnerung konstruierter (auch fiktiver), physikalischer Objekte

o zwei Herangehensweisen an die menschliche Existenz, deren Weg nicht kontrolliert werden kann, aber deren Verständnis ständig erweitert werden kann, mit dem Leben, das aus unterschiedlichen Facetten zusammengefügt ist, äußeren Einflüssen unterliegt und sich in Bewegung befindet; Teil dessen seiend kann akzeptiert werden oder wir können und mit der Anpassung abmühen – die vergänglich und illusorisch ist

SHANGHAI GALLERY OF ART, THREE ON THE BUND

- Adresse: 3rd Floor, No.3, the Bund 中山东一路三号三楼, 021-6321 5757, 6323 3355

- gegründet 2004 mit dem Anspruch, wichtige cn. Ggwts.künstler zurück nach China zu holen, um die Geschichte Chinas zu bewahren

- aktuelle Ausstellung: Feng Mengbo „Journey to the West“ (Beijing, 1966); einige Hintergrundinformationen zum Künstler:

o Feng Mengbo ist ein Video- und Installationskünstler

o seine Arbeit „Q4U“, eine künstlerisch bearbeitete Version des Egoshooters Quake III, war 2002 auf der Documenta zu sehen

o 2004 wurde ihm der Kulturpreis Prix Ars Electronica für „Ah_Q – A Mirror of Death“ überreicht

o „Die Reise in den Westen“ ist einer der chin. literarischen Klassiker (insg. 4, dieser aus der Ming-Dynastie im 16. Jhd. von Wu Cheng’en)

--> Geschichte der Reise des Mönches Xuanzang zum westlichen Himmel, im heutigen Indien, von wo er Buddhas heilige Schriften nach China bringen soll – reale Begebenheit aus dem 7. Jhd.; begleitet wird er von Gefährten, von einem Wasserdämon, einem Menschen, der in ein Schwein verwandelt wurde und vom König der Affen Sun Wukong – dem eigentlichen Hauptcharakter der Geschichte

o Zus.fügung aus seinem Interesse an digitaler Kunst und Tradition, klassische spirituelle Werte sind überführt in die Cyberrealität Fengs

o idyllische Landschaften sind mit 3D-Programmen bearbeitet, dazu kommt ein interaktives Videospiel mit Gaming Hard- und Software

o Themen: Kommerz, Tradition

Three on the Bund mit Blick über den Bund

STUDIOBESUCH VON WU SHANZHUAN UND INGA SVALA THORSDOTTIR, PUDONG

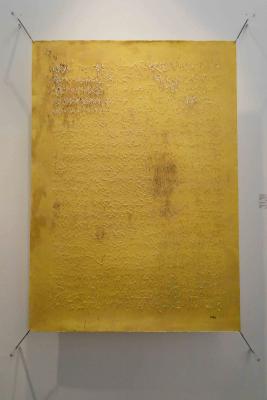

- Wu Shanzhuan (Zhoushan, 1960, lebt in Hamburg und Shanghai), spricht Dt. und Engl.

- international anerkannter Konzeptkünstler, ein Freund von Bruno Bischofberger

- bekannt als einer der Vorreiter der cn. Konzeptbewegung in den 1980ern, war Wu der erste Künstler in China, der Textteile von Popanspielungen in seine Werke aufgenommen hat. Damals kristallisierte sich auch sein äußerst idiosynkratischer Ansatz der Malerei heraus, den er mit politischen Aussagen, religiösen Schriften und Werbeslogans kombiniert

- Wus Leinwände erscheinen als eine Kombination aus Graffiti und Expressionismus; zus.gefügt aus Wörtern, Symbolen, Diagrammen, die um den Platz auf seinen Werken zu wetteifern scheinen – virtuell auf der Wand und in piktografischer Abstraktion

- durch die Verwendung der Symbole entzieht er ihnen ihren urspr. Kontext und ihre kulturelle Bedeutung – wobei diese natürlich immer oberflächlich mitspielen –, er entleert sie durch den Massengebrauch an Farbe und Schrift, reinigt sie für den Neugebrauch und zur Kontemplation

- Wu geht den Prozess des Malens als Schreiben, exemplarisch etwa in seiner Serie „Today No Water“ von 2007. Als grafischer Roman angelegt, bildet jede Leinwand ein Kapitel einer sich aufbauenden Erzählung. Zugrunde liegt dem keine Storyline, sondern vielmehr eine visuelle Spannkraft zwischen fragmentarischen Phrasen und Bildern, die in einer Gesamtkomposition von Freestyle Assoziationen und Ideen, Referenzen und Symbolen zus.kommen

MOGANSHAN ART DISTRICT

- Adresse: 普陀区莫干山路50号

- das Moganshan, genannt M50 nach seiner Lage auf der Moganshan Road Nr. 50, ist das Künstlerviertel von Shanghai – ähnlich dem 798 in Beijing

- vor 10 Jahren zogen die ersten Künstler und Galerien in eine alte Textilfabrik in das Moganshan 50. Der Komplex war jahrelang vom Abriss bedroht, während sich in nächster Nachbarschaft Hochhäuser in die Höhe schraubten. In den letzten Jahren entwickelte sich dann in der 50 Moganshan Road eine Kunstoase, die schließlich immer kommerzieller wurde und dadurch ihr Bestehen sichern konnte

- das 10. Jubiläum des Viertels beginnt seine Eröffnungsfeier heute und geht bis in den Oktober hinein

- ShanghART, Shanghai, Beijing

o initiiert 1996 von Lorenz Helbling, gilt als eine der einflussreichsten Institutionen der Ggwts.kunst in China

o aktuelle Ausstellungen:

--> Sun Xun (Fuxin, 1980): New Media-Künstler; produziert eine Vielzahl von Werken, die Textpassagen in den Bildern seiner Anima aufnehmen; er beschäftigt sich mit Weltgeschichte und Politik, sowie mit lebenden Organismen

--> Zhao Bandi (BJ, 1966): bekannt für seine Panda-Serien als Parodie auf die offizielle cn. Propaganda, durch das Nationaltier spricht Zhao auch auf der ShContemporary unter den „Discoveries“, dort hat er seine Werke von den beiden Kindern vorstellen lassen

o. A.

Madeln „Spread 201009103“ (2010)

Ding Yi „Appearance of Crosses 2007-8-04/ 01/ 03“ (v.l.n.r., 2007)

Yang Zhenzhong „No. 01 – No. 25“ (2010)

- Galerieempfehlungen zum 10. Jub. des M50

o Loh Gallery, Moganshan Bldg. 3/ 111: Galerieeröffnung 19 Uhr

o Madeln Space, Moganshan Bldg. 7/ 4. Stk., Eröffnung Li Ming, Lin Ke, Yang Junling: „Dedicated to Money Makers“, 18 Uhr

o Vanguard Gallery, Moganshan Bldg. 4A/ 204, Ausstellung Xu Di: „Vivid as Fruit“

Samstag, 11. September 2010

PRIVATSAMMLUNG VON QIAO ZHIBIN

- Sammler mit eigenen KTV-Clubs in Beijing und Shanghai

Ding Yi

Zeng Fanzhi

Aoyama Satoru

MINSHENG ART MUSEUM/ RED TOWN

- Adresse: Red Town, 570 Huaihai Xi Lu, Xuhui District 淮海西路570号,近凯旋路, Tel: 021-6280-4741, 6280-9231

o wie das Rockbund ist das Minsheng ein neues Museum mit der zweiten Ausstellung.

Es ist benannt nach seinem „Gründer“, der Minsheng Bank – das Museum ist das erste seiner Art in China, das von einer Bank gegründet wurde. Die erste Ausstellung hatte sehr große Ziele verfolgt, es handelte sich um eine Retrospektive der chin. Kunst der letzten 30 Jahre – leider wirkte es etwas willkürlich bzw. schien es, als wären die Werke ausgestellt, die gerade zur Verfügung standen oder von befreundeten Künstlern zur Verfügung gestellt wurden

- aktuelle Ausstellung: Korean Contemporary Art „Plastic Garden“

o „Plastic Garden“ ist eine Ausstellung von 17 koreanischen Künstlern mit 64 Werken

o Gemeinsamkeiten liegen eindeutig in der verbindenden asiatischen Tradition der Kalligraphie und des kontemplativen, buddhistischen Ansatzes; in der Vorstellung der Lehre des Nichts

Noh Sang Kyoon

Yongbaek Lee

Lee Seahyun

Chung Suejin

Jung Yeondoo

Ham Jin

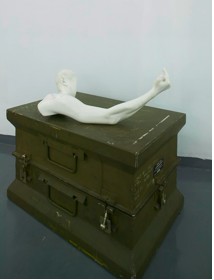

RED TOWN: „SCULPTURE PARK“ UND „SCULPTURE SPACE“

- Regelmäßig wechselnde Skulpturen

- Red Town war urspr. eine Stahlfabrik und ist seit seiner „Neugründung“ 2005 zu einer der Zentren der Kreativindustrie Shanghais geworden (mit allem, was dazugehört, Designfirmen, Cafés, Galerien etc.)

WEITERE GALERIEN

- 140 sqm

o Galerie von Liu Yingmei, aktuell: Ai Weiwei und Zhang Peili

o Adresse: 1331 Fuxing Zhonglu, 26 Room, near Fenyang Lu 复兴中路1331号26室,汾阳路口, 021-6431 6216

- Zendai Himalayan Art Center

o aktuell: „Updating China for a Sustainable Future“ (dt.-cn. EXPO-Show)

o No. 28 Lane 199, Fangdian Lu 芳甸路199弄28号, 021-5033 9801

- MoCA Shanghai

o aktuell: Umbau für Eröffnung „Reflection of Minds“ am 12.9.

o Adresse: People's Park, 231 Nanjing West Road 人民公园南京西路231号,021-6327 9900

- Shanghai Duolun Museum of Modern Art

o aktuell: Saudi Arabien

o Adresse: No. 27 Duolun Road 多伦路27号, 021-6587 2530, 6587 5996

- Zhu Qizhan Art Museum

o aktuell: Poetry of Russian Soul

o Adresse: No. 580 Ouyang Road, 欧阳路580号, 021-5671 0742, 5671 0741

140sqm: Ai Weiweis Skulptur zur „Fuck Off“-Fotografieserie (2006)

Fan Jiupeng (2010)

Art Labor Gallery: Ying Yefus „Sweet and Sour“ (2010)

Tags für diesen Beitrag 这本文章的标记: Reise 专程, Künstler 艺术家, Ausstellung 展览, Gegenwart 当代, Häufig gelesen 频看

... link (0 Kommentare) ... comment

Mittwoch, 17. November 2010

Auf Kunstreise in Beijing

youjia, 13:22h

Hier ein paar weitere Eindrücke der Kunstreise durch Shanghai und Beijing vom 8.-14. September 2010 – und nun Beijing, kürzer gehalten, vermutlich weil von mir allgemein abgegraster:

Sonntag, 12. September

Zunächst ein paar Sehenswürdigkeiten auf der Nord-Süd-Achse:

(Quelle: chinaodyseeytours.com, 21.2.09)

1. Qianmen („Das vordere Tor“)

2. Platz des himmlischen Friedens, Tian’anmen

--> Vom Qianmen ausgehend, das „Mao Mausoleum“, links der „Großen Halle des Volkes“, rechts dem „Museum der chin. Revolution und Geschichte“ über den „Platz des Himmlischen Friedens“ am „Denkmal für die Volkshelden“ (38 m hohe Stele in der Mitte des Platzes) Richtung „Verbotene Stadt“ – Symmetrie und Planung, rot/ gelb, Nord-Süd-Achse, Regierungsviertel

„Zhongnanhai“

3. Nationaltheater/ „Entenei“ (Paul Andreu)

4. Vorbei an der Verbotenen Stadt, Nan Chizi

5. Am Meishuguan (NAMOC) vorbei hoch, vorbei am See Houhai zum Trommelturm

6. „Olympic Green“ mit „Vogelnest“ (Herzog & deMeuron) und „Watercube“ (PTW)

Anschließende Fahrt ins 798:

PACE GALLERY

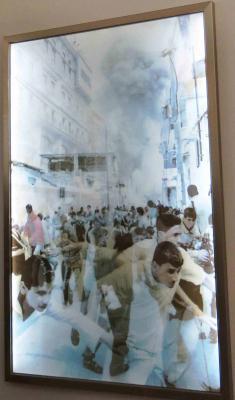

- aktuelle Ausstellung: Performance Art der 1990er-Jahre in China

- die Performance als Medium „to push […] art to the edge of reality […] to seem surreal“

o Featuring: Duan Jianyu, Hai Bo, He An, He Yunchang, Hu Xiangqian, Liu Yilin, Liu Wei, Liu Xiaodong, Ma Liuming, Ma Qiusha, Qin Ga, Qiu Zhijie, Song Dong, Sun Yuan & Peng Yu, Wang Jin, Wang Qingsong, Wu Daxin, Wu Xiaojun, Xiao Yu, Xu Zhen, Yang Fudong, Yang Maoyuan, Yang Zhichao, Yuan Shun, Zhan Wang, Zhang Dali, Zhang Huan, Zhao Bandi, Zhuo Tiehai, Zhu Fadong, Zhu Yu

TANG CONTEMPORARY

- aktuelle Ausstellung: Zheng Guogu, Chen Zaiyan, Sun Qinglin „Garden of Pine – Also Fierce Than Tiger II“

o die drei Anfang der 1970er-Jahre in Yangjiang/ Guangdong geborenen Künstler sind bekannt unter dem Namen „Yangjiang-Gruppe“, gegründet 2002 (bis 2005 Yangjiang Calligraphy Group)

LONG MARCH GALLERY

- aktuelle Gruppenausstellung: „Long March Project – Ho Chi Minh Trail“

(Quelle: Long March Project, Stand: 18.9.10)

ULLENS CENTER FOR CONTEMPORARY ART UCCA

- aktuelle Ausstellung (u. a.): Zhang Huan „Hope Tunnel“

o im Zuge des schweren Erdbebens im Mai 2008 in Sichuan sind dies die Überbleibsel des mit kerosinhaltigem Material beladenen Transportzuges, der im Tunnel vom Beben überrascht wurde, und die Zhang Huan vor der Stahlschmelze als Gedenken retten konnte

Zhang Huans „Hope Tunnel“

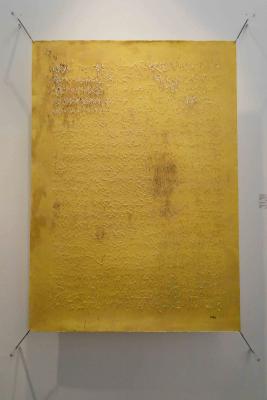

Yu Hongs „Golden Sky“

Dienstag, 14. September

URS MEILE GALLERY

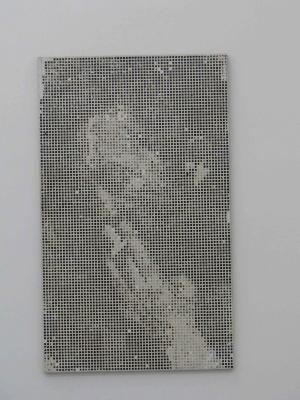

- aktuelle Ausstellung: Shan Fan „Homeland: Painting the Moment – Peinting Slowness“

o „China, a society which turned the written word itself into the most elevated of art forms and used that calligraphy aesthetic to create a complex whole connected by a sophisticated political and symbolic abstract spirituality.“

Shan Fan, Komposition und Zoom

Xiao Wan

Qiu Shihua

BESICHTIGUNG DER KÜNSTLERSTUDIOS VON

Zeng Fanzhi

Qiu Zhijie

Lin Tianmiao und Wang Gongxin

BESICHTIGUNG WEITERER GALERIEN IM CAOCHANGDI

Caochangdi: Das Original von Ai Weiwei (oben) und der „Nachbau“ in unmittelbarer Nähe

- Three Shadows Gallery

o Fotografiezentrum von Rong Rong und inri

- Platform China

- White Space Beijing

- Alexander Ochs Galleries

- etc.

Three Shadows Gallery (das Foto ist allerdings von 2009, die Granatapfelbäume mussten dieses Jahr bis auf den Stamm heruntergeschnitten werden, was ziemlich traurig aussieht – aber sie treiben wieder)

Aktuelle Ausstellung im Three Shadow: Rong Rong und inri

Platform China

Aktuelle Ausstellung im Platform: Xie Xiaobings „Just only for an ideal“ (2010)

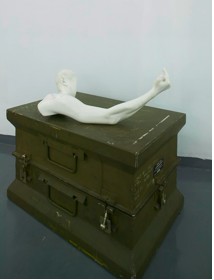

Pei & Lei Gallery: Wang Zhijies „Little Girl“ (2009)

Tags für diesen Beitrag 这本文章的标记: Reise 专程, Künstler 艺术家, Ausstellung 展览, Gegenwart 当代, Häufig gelesen 频看

Sonntag, 12. September

Zunächst ein paar Sehenswürdigkeiten auf der Nord-Süd-Achse:

(Quelle: chinaodyseeytours.com, 21.2.09)

1. Qianmen („Das vordere Tor“)

2. Platz des himmlischen Friedens, Tian’anmen

--> Vom Qianmen ausgehend, das „Mao Mausoleum“, links der „Großen Halle des Volkes“, rechts dem „Museum der chin. Revolution und Geschichte“ über den „Platz des Himmlischen Friedens“ am „Denkmal für die Volkshelden“ (38 m hohe Stele in der Mitte des Platzes) Richtung „Verbotene Stadt“ – Symmetrie und Planung, rot/ gelb, Nord-Süd-Achse, Regierungsviertel

„Zhongnanhai“

3. Nationaltheater/ „Entenei“ (Paul Andreu)

4. Vorbei an der Verbotenen Stadt, Nan Chizi

5. Am Meishuguan (NAMOC) vorbei hoch, vorbei am See Houhai zum Trommelturm

6. „Olympic Green“ mit „Vogelnest“ (Herzog & deMeuron) und „Watercube“ (PTW)

Anschließende Fahrt ins 798:

PACE GALLERY

- aktuelle Ausstellung: Performance Art der 1990er-Jahre in China

- die Performance als Medium „to push […] art to the edge of reality […] to seem surreal“

o Featuring: Duan Jianyu, Hai Bo, He An, He Yunchang, Hu Xiangqian, Liu Yilin, Liu Wei, Liu Xiaodong, Ma Liuming, Ma Qiusha, Qin Ga, Qiu Zhijie, Song Dong, Sun Yuan & Peng Yu, Wang Jin, Wang Qingsong, Wu Daxin, Wu Xiaojun, Xiao Yu, Xu Zhen, Yang Fudong, Yang Maoyuan, Yang Zhichao, Yuan Shun, Zhan Wang, Zhang Dali, Zhang Huan, Zhao Bandi, Zhuo Tiehai, Zhu Fadong, Zhu Yu

TANG CONTEMPORARY

- aktuelle Ausstellung: Zheng Guogu, Chen Zaiyan, Sun Qinglin „Garden of Pine – Also Fierce Than Tiger II“

o die drei Anfang der 1970er-Jahre in Yangjiang/ Guangdong geborenen Künstler sind bekannt unter dem Namen „Yangjiang-Gruppe“, gegründet 2002 (bis 2005 Yangjiang Calligraphy Group)

LONG MARCH GALLERY

- aktuelle Gruppenausstellung: „Long March Project – Ho Chi Minh Trail“

(Quelle: Long March Project, Stand: 18.9.10)

ULLENS CENTER FOR CONTEMPORARY ART UCCA

- aktuelle Ausstellung (u. a.): Zhang Huan „Hope Tunnel“

o im Zuge des schweren Erdbebens im Mai 2008 in Sichuan sind dies die Überbleibsel des mit kerosinhaltigem Material beladenen Transportzuges, der im Tunnel vom Beben überrascht wurde, und die Zhang Huan vor der Stahlschmelze als Gedenken retten konnte

Zhang Huans „Hope Tunnel“

Yu Hongs „Golden Sky“

Dienstag, 14. September

URS MEILE GALLERY

- aktuelle Ausstellung: Shan Fan „Homeland: Painting the Moment – Peinting Slowness“

o „China, a society which turned the written word itself into the most elevated of art forms and used that calligraphy aesthetic to create a complex whole connected by a sophisticated political and symbolic abstract spirituality.“

Shan Fan, Komposition und Zoom

Xiao Wan

Qiu Shihua

BESICHTIGUNG DER KÜNSTLERSTUDIOS VON

Zeng Fanzhi

Qiu Zhijie

Lin Tianmiao und Wang Gongxin

BESICHTIGUNG WEITERER GALERIEN IM CAOCHANGDI

Caochangdi: Das Original von Ai Weiwei (oben) und der „Nachbau“ in unmittelbarer Nähe

- Three Shadows Gallery

o Fotografiezentrum von Rong Rong und inri

- Platform China

- White Space Beijing

- Alexander Ochs Galleries

- etc.

Three Shadows Gallery (das Foto ist allerdings von 2009, die Granatapfelbäume mussten dieses Jahr bis auf den Stamm heruntergeschnitten werden, was ziemlich traurig aussieht – aber sie treiben wieder)

Aktuelle Ausstellung im Three Shadow: Rong Rong und inri

Platform China

Aktuelle Ausstellung im Platform: Xie Xiaobings „Just only for an ideal“ (2010)

Pei & Lei Gallery: Wang Zhijies „Little Girl“ (2009)

Tags für diesen Beitrag 这本文章的标记: Reise 专程, Künstler 艺术家, Ausstellung 展览, Gegenwart 当代, Häufig gelesen 频看

... link (0 Kommentare) ... comment

Sonntag, 19. September 2010

Mo., Sept. 20, "Meet & Greet"

youjia, 10:49h

If you happen to be in Shanghai on Monday and want to know about the "Future of Creative Industry", check this out, 7 pm at MoCA:

Please register via: vivianyutianzheng@gmail.com.

Tags für diesen Beitrag 这本文章的标记: Ankündigung 通知, Gegenwart 当代

Please register via: vivianyutianzheng@gmail.com.

Tags für diesen Beitrag 这本文章的标记: Ankündigung 通知, Gegenwart 当代

... link (0 Kommentare) ... comment

Mittwoch, 12. Mai 2010

Huang Rui über Abriss von Kunstvierteln in Beijing

youjia, 06:47h

Per E-Mail hat auch mich jetzt der Mitte Februar verschickte Artikel von Huang Rui 黄锐 (Mitglied der Gruppe Neue Sterne von 1979 und einer der Gründer von 798) erreicht. Recht lang, aber ich habe ihn im Netz noch nicht vollständig gefunden.

A City that Abandoned Artists

By HUANG Rui

Winter in Beijing is Especially Cold

After the 2008 “New Beijing, New Olympics,” in July 2009, Chaoyang District in the city of Beijing held the Chaoyang District Work Mobilization Conference to Promote Land Reserves and the Unification of Urban and Rural Areas. The conference resolved to promote the unification of the city and the countryside by reclaiming 26.2 square kilometers of countryside for the city land reserve. This area included seven villages in Dongba, Cuigezhuang, Sunhe, and Jinzhan. Regardless of whether these areas were pastures, fields, residential areas, or construction sites, they were all incorporated into the new urban expansion plan. Since the beginning of winter, any structure on this land has been demolished or is scheduled to be demolished; this single area includes nearly twenty art districts.

This year, winter in Beijing was especially cold. Following the largest blizzard in fifty years, many art districts faced forced evictions and the loss of electricity, water, and heat.

Chaoyang District is using the same kinds of methods as local governments nationwide; it has resorted to making money with land. The larger policy of economic development is meant to expand government interests. There is no need for further discussion of our doubt about and criticism of these basic policies. However, because Chaoyang District's current policy of demolishing buildings and moving residents involves nearly twenty art districts and more than one thousand artists, it is hurting a primary artery of cultural life in Beijing. Chaoyang District is also endangering the interests of the entirety of Chinese contemporary art, and so it has become a problem that urgently needs a solution.

These economic justifications are inadequate because China’s development drives the development of urban economies and culture. After the legal issues related to the 798 Art District were resolved by the Beijing municipal government, art districts such as the Liquor Factory, Huantie, Dongying, Zhengyang, 008, Caochangdi, and No. 1 Artbase all publicly responded to the local government’s land development plans. Residents of the districts personally invested in their construction. This expanded Beijing’s 798, this newly-established art district that had the halo of “21st century urban business card.”[1]

As for the impact of this decision, what recourse did the over one thousand artists who lost their livelihoods and their work spaces have? The response from the district government was simply a series of perfunctory and evasive phrases like “urban development program” and “complying with land law.”

Continuously Dissimilating Land

It is strange that while the art districts were being demolished, some called into question the legality of art districts, but no one over questioned the legality of the government’s decision. When the government demolition teams were invading the art districts with all their equipment, the artists all thought they had been tricked by the developers. Therefore, in public opinion, the government’s decrees became a substitute for what is lawful. Though this is a tragic situation, artists would rather deal with the government; it is the profit-seeking nature of developers that overturns the legitimacy of the space. But, if you only see the big heading “Chaoyang District Work Mobilization Conference to Promote Land Reserves and the Unification of Urban and Rural Areas,” then you know only part of the story. This heading is a government trick to transform the nature of land. In the past, the areas where the city and countryside met were not worth anything, but in the last thirty years, the majority of these areas have undergone the following stages of development. What started as farmland became green spaces to meet green targets for the City of Beijing. As a result, the value of this land increased slightly. Next, the land doubled as a green space and as a place for small-scale production or even recycling, and so it once again increased in value. Until after the neighborhood around the 798 became an urban phenomenon, many art districts appeared to the east and the north of 798. Around this time, the trend for land income to be changed to real estate income began. As before, these areas were collectively operated, they were not included in actions by the city. Therefore, the city did not benefit and government officials did not have achievements to report. Presently, collective ownership under the original policy in which land was divided by family has been changed to public ownership, which is defined in the constitution as “city land is state-owned.” In development plans for urban expansion, cities can turn what was originally farmland into public or commercial land to be sold at auction. Farmers on collective land all became city residents and accepted compensation at 21st century levels. In this Chaoyang District land conversion movement, nearly 110,000 farmers have traded a standard one-time payment for land that could earn them money year-round. You can see their calm and reserve as they quietly accept the

facts, like winter snowflakes falling to earth.

Art Space is Unreal

So why do artists continue to stay in the grey areas called art districts? They stay because of the unique nature of the artists’ profession. Art itself does not produce reality; artworks are the reappearance of the combination of skills and materials, intended to construct an idealized scene for the viewer. In fact, the distance created between artworks and reality or the opening of a new path has become the charm of artworks. It is exactly for this reason that artists are not interested in well-regulated space, such as one would find in a normal residential area; the atmosphere of the space could pull artistic creation back to reality.

China’s present conditions still have not created a true art market. Quantities of artworks, the tastes of collectors, estimations of value, and the shortcomings of the critical world are all impediments to the normal operation of an art market. To satisfy the ferocious appetite of speculators, artists continuously produce large works. Only large works can be exhibited in large spaces and retain the imposing “Made in China” air. This production method also determines that artists will favor large spaces like factories or warehouses. These kinds of spaces are easy to manage, because works can enter and leave freely, light is plentiful, and the surroundings have few of the impediments of common life. Why do artists all like to gather together to work? This is also due to the unique characteristics of urban society. First, space is scarce in cities, and there are only a few kinds of space from which to choose. Second, there is pressure from the neighborhood or the street. Generally, organized neighborhoods are not tolerant of different people and special circumstances. Third, there are legal issues. Artists are scattered individuals, but in reality they are a group that requires support in areas of legal and institutional uncertainty, and so artists think that the individual is powerless. They often make decisions based on the surface-level and inessential aspects of things, or they rely on the judgments of friends as a reference. Artists in many art districts may be from the same school or hometown.

However, artists’ lack of pragmatism about the law does not prove the soundness and rationality of the law and reality.

“We Don’t Need Artists Here! Get Out!”

This slogan was written in white on a wall along the road in the 798 Art District. It is especially eye-catching, hasty, and powerfully authentic, because it was placed across from several pledges by artists to protect their space in the art district. Things like this really do happen. This sentence, “We don’t need artists here” came from innocent emotion, which makes us think of the slogans from the 1960s and 1970s. “Purify the ranks of the proletariat!” Workers and farmers with revolutionary consciousness but no education were the primary motivation behind the Cultural Revolution. Perhaps this was true at that time, so we cannot help but rub our eyes and re-identify the present era. It is hard to believe that this state of affairs is real. We are once again clearly differentiating social identities. “We don’t need artists here!” Please do not doubt that this is currently happening. A large group of artists was chased into the wilderness during the coldest of times. They call out as they run. During the Warm Winter Art Program, they became the rogue proletariat. Mao Zedong once said that they were the class most unworthy of trust. “Once bought, they will become the enemies of the revolution.” We can compare these two governments which have produced different eras and these two movements, both of which consider artists garbage to be swept out the door. The former did it for the revolution; the latter has done it for capital. Because it is popular with the masses, the threat of capital is just as Walter Benjamin described movies, “All of the interest that the masses show in films is an interest in the recognition of the self and one’s class; which all suffer from a degenerative distortion.”[2]

Polish workers during the Cold War, disgusted with student demonstrations requesting freedom, had their own slogan “We want freedom, but we want bread more.” In the mid-1980s, under the guidance of the United Trade Union, they changed the slogan to “We want bread, but we want freedom more.”

Development has been swift, and Beijing, the capital of what was thirty years ago an agricultural nation, had already entered a period of rapid urbanization, a period of commodity circulation and information culture. And this Beijing is “the model for several hundred Chinese large and medium-sized cities, but in the future there will be more than one thousand of these cities.”[3] In response to the requirements of the new age, artists and all creators, including the presenters of creation, should increasingly become the masters of this new scene. We believe that we need only to strengthen the ranks of artists to make China better. Artists are distant from quality, standards, roles, judgment. They are the closest to illusion. We might as well start now, using the palette of glorious color and light of a harmonious society to affirm that artists are an advanced “class” with the time for advanced “productivity.”

Destruction in the Name of Success

Last year the People’s Republic of China held its 60th anniversary celebration, and I saw a familiar scene. I became a Young Pioneer or a Red Guard being inspected who had seen the leader Mao Zedong four times with my own eyes. As before, he stood, centered atop the Tian’anmen Gate, watching the fully equipped masses. What is amazing is that the revolutionary miracle that Mao had achieved was covered by another miracle that year; China had already become the world’s second most powerful economic force, and it will become the first before long. On this day, perhaps it was the dream of Mao as victor on Tian’anmen Gate.

However, if the miracles brought by creation and production are amazing, the power of destruction has also been uniquely successful. Because of the example of Mao Zedong’s era, we know that the success of Mao Zedong’s revolution brought about a disastrous destruction of productivity. He once said, “There is no construction without destruction. Destroy first, and construction will follow.” Mao and the political system that Mao founded more than thirty years ago are identical in their pursuit of success and victory. Even if they have different ideals, are all oriented towards one thing, success.

Those who believe in the cyclicality of history should once again refer to facts that can only be seen briefly. Taking Beijing as an example, the urbanization movements of the 1950s and 1960s not only tore down the Ming and Qing Dynasty city walls that had been criticized by the people, they also demolished a Yuan Dynasty temple that was more than 500 years old.[4] The religion, culture, and art transmitted by the temple were certainly the essence of Chinese civilization. It was this cultural ecology that made Beijing preeminent, but it no longer exists. In the thirty years since Reform and Opening, Chinese industrial civilization has made tremendous advances, and the people have started to experience unprecedented happiness and material comfort. But the reality behind the cultural structure of old Beijing then opened into the period of architectural foundations for the “New Beijing, New Olympics.” All kinds of inconveniences appeared in society, and very seldom were there people to challenge or to mention the destruction of this cultural ecology. In the media you often see “the destruction of the natural ecology,” likewise the natural and cultural ecologies formed in the course of history supports the spiritual ecology of city residents. All ecologies are mutually linked, complementing each other. In the Dao De Jing, Lao Zi says, “Misfortune depends on fortune. Fortune conceals misfortune.” The price of this new round of urban expansion is certainly a new round of environmental disasters.

Whose Cultural Ecology?

Our city has become an even more complex organization of skin and blood vessels. There are countless categories and systems of materials, production, products, circulation, order, emotion, exchange, belief, individual, family, organization, and society. But the manager of every field is a single thought, which is related to the value system of capital markets; the pure numbers of every field have an exchange value. Thus, the standards for sustainable ecology are like the ethical standards for justice, they cannot be produced by the market. The market's only formula is unit price (number) x efficiency x scale, while the calculations for ecological standards are completely the opposite. Perhaps these ecological relationships are still cannot be calculated by one or two clearly understood formulas, so we must wait for the inventions of researchers. But I believe that if emotions, organisms, and rationality are interwoven in urban life for a long period of time, you will certainly feel its presence, like the scene in the movie Avatar where life is summoned back. Ecological research, as a synthetic, interdisciplinary, newly established branch of learning, is still maturing. Whitman said in a poem, “Or I guess it is the handkerchief of the Lord, / A scented gift and remembrancer designedly dropt, / Bearing the owner’s name someway in the corners, that we / may see and remark, and say Whose?”[5]

“It Takes a Decade to Grow a Tree; It Takes a Century to Cultivate a Talented Person”

It has taken Caochangdi ten years to develop to its present state. The eventual rise of the 798 can be traced back to the temporary movement of CAFA’s sculpture department in 1995. As the Chinese saying goes, “It takes a decade to grow a tree; it takes a century to cultivate a talented person.” The ecology gradually formed in Chaoyang district by the 798, Caochangdi, and more than twenty other art districts is the pride of the area; it is an opportunity for history to bestow favor upon the City of Beijing. These chance opportunities involve extremely rational natural factors; is this not the “timeliness, favorable geography, and popularity” on the lips of the influential figures in these important demolition movements? Now, are the ecologies formed outside their plans not the cultural vegetation of Chaoyang District, the City of Beijing, and China as a whole? Please look at the disorderly construction of bare neighboring cities that have no cultural vegetation. Please look the places that have been abandoned by artists. Regardless of whether you look at Tianjin, Shijiazhuang, Baoding, Hubei, Sichuan, or Yunnan, just notice the population ratios between these areas and Beijing and the ratios between population and GDP and you will understand. Even if an area is fanatical about administration, the lack of cultural vegetation is a state of desolation akin to Huoyan Mountain. The linking of economic powers also needs the protection of cultural vegetation. Naturally formed cultural conditions can have a rational structure. The more intrinsic this structure and the more haphazardly it is created, the stronger its objective appeal. The majority of artists have said goodbye to their hometowns and come to this new land to live. And now, a drastic decision has cut their lifelines, using bulldozers to crush art spaces to and causing artists to move out into the cold streets and become a nomadic group. Is this an ordinary occurrence in our harmonious society? Can our city afford to abandon such a large number of artists?

If we can use economic capacity to build a forest of cement and glass walls and if we can use modern green methods to gloss over the ecology of “growing a tree in a decade” (and there are even doubts about our ability to do this), then can our local governments create the conditions to nurture talented people? The government can easily seek applicants for more than a thousand positions in construction or policing, but what about the thousands of artists who have gathered together in pursuit of human ideals? Please look; they do not have any administrative support. The construction of art spaces driven by economic gain is completely different from the surrounding environment. If you look at the intact Caochangdi Art District, you will understand what can be called life or subsistence; you will understand the difference between quality and quantity, vitality and chaos, development and sustainable development. The Caochangdi Art District has already provided a nearly standard solution.

I invite those planners who are advocates of demolition to walk in the art district on a clear morning; just go see the art spaces, you do not need any specialized knowledge of art.

Building Standards in Caochangdi